I did a presentation at the Concrete Bridge Development Group annual conference yesterday on my current pet subject “Decarbonising concrete – are low carbon concretes the solution or part of the problem”. It seemed to go down pretty well.

I am reproducing the associated paper here to hopefully start a discussion on the use of the concept of opportunity carbon cost. This is Part 1 which explains why high levels of slag addition in concrete is actually increasing carbon emissions and proposes a methodology for calculating embodied carbon which could rectify this waste of a valuable resource. Part 2, which will be posted later, looks at measures that could be implemented to reduce embodied carbon contents of concrete.

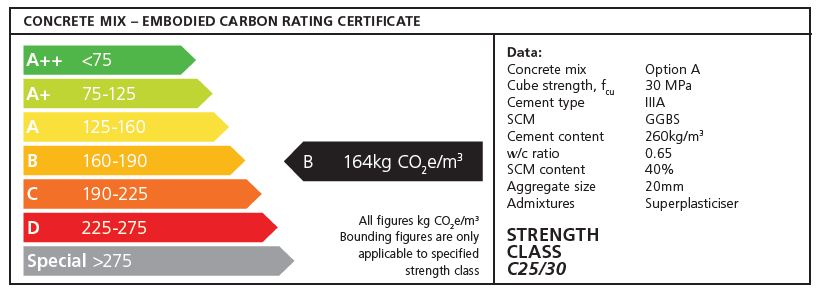

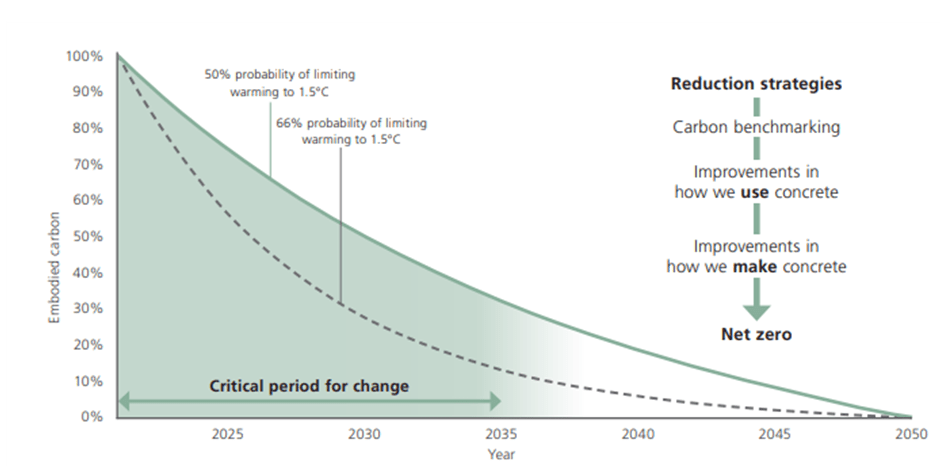

The drive to use low carbon concrete is gathering pace. New products are coming to market. Clients are demanding more sustainable projects. The proposed Lower Thames Crossing is leading the way in this aspiration, with National Highways designating it a ‘pathfinder’ project that will explore carbon neutral construction as part of its efforts to make the new crossing the greenest road ever built in the UK . Guidance on how to reduce carbon emissions in concrete has recently been published by ICE and the Green Construction Board , which includes a benchmarking system, similar to that found on domestic electrical appliances (Figure 1), which aims to encourage clients and engineers to reduce carbon contents.

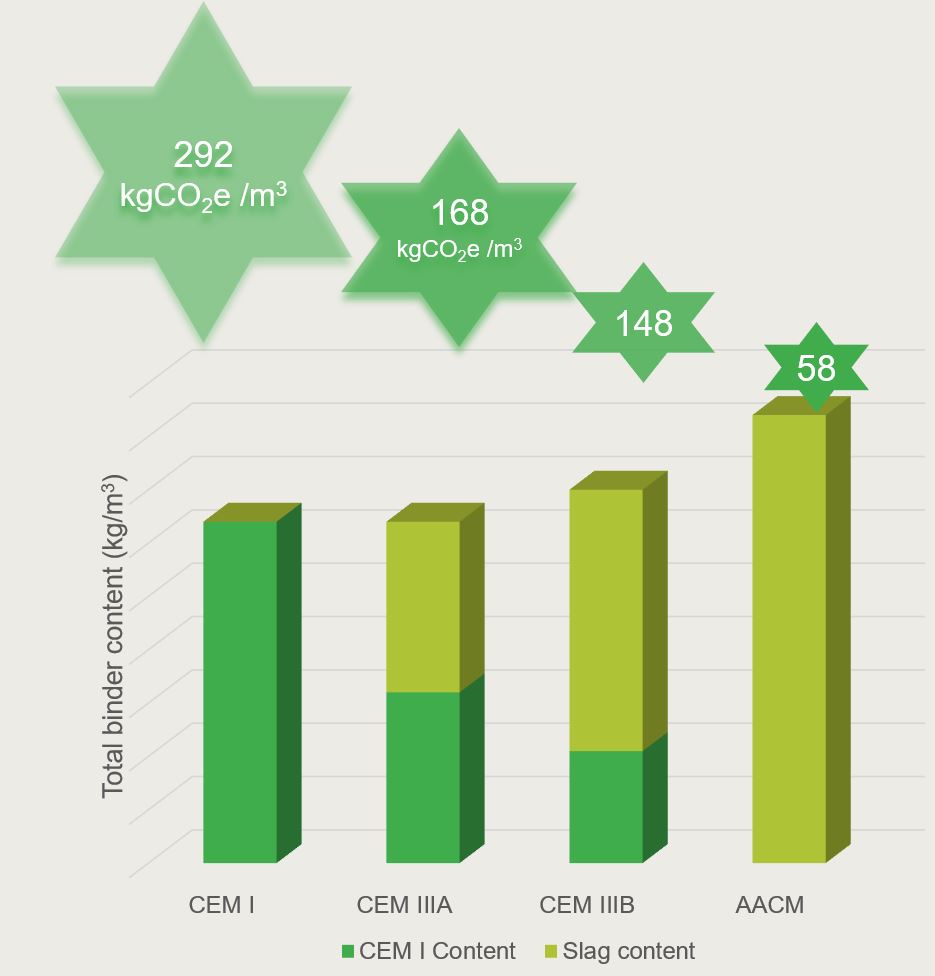

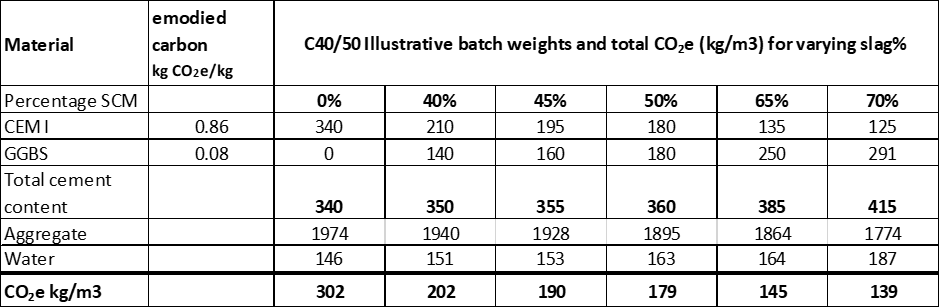

MPA Fact Sheet 18 provides emissions data on UK cements and supplementary cementitious materials. Due to the very low embodied carbon content of supplementary cementitious materials (SCM) like fly ash and ground granulated blastfurnace slag (ggbs) relative to CEM I, it can be easily demonstrated that partial replacement of CEM I by a SCM will reduce the carbon content of concrete. Increasing the percentage of SCM will reduce early age strengths but increase later age so it is most efficient, economic and sustainable to specify these mixes with compliance ages for characteristic strength at 56 or even 90 days instead of the usual 28 days. Even allowing for increases in total cementitious content to maintain 28 day strengths, the embodied carbon content of the concrete will be lower with high levels of SCM (see Table 1).

Note:

The batch weights shown in this table are indicative and have been derived from a combination of actual mix designs used on current projects on which the author is involved, some laboratory test data and some engineering judgement.

There are many factors to consider when developing mix designs, but the data in Table 1 illustrates that despite increasing cementitious content by over 20% to maintain 28 day strengths, the carbon content has still been reduced by over 50%.

The use of high levels of slag would seem to be the obvious solution for improving the sustainability of concrete. While there are many advantages to using very high slag contents there are also some significant disadvantages. High slag contents offer durability improvements (particularly in chloride and sulfate resistance) and in reducing the early-age heat of hydration and the consequential risk of thermal cracking. However, the slow rate of hydration also reduces the early-age strength of the concrete which can delay formwork removal times significantly and lead to longer construction programmes. For this reason, high levels of slag are not suited in particularly to the precast industry, which relies on rapid turnaround of formwork. These considerations may impact the level of slag specified in concrete.

- Reduce risk of alkali-silica reaction: BS 8500-2 Table 1 states that the alkali content of slag need not be considered in the calculations if it constitutes not less than 40% of the total cementitious content; 50% of the alkali content should be included in the calculations if slag content is between 25 and 39% and 100% if slag content is less than 25%.

- As the percentage slag increases, the heat of hydration is reduced but so is the rate of strength gain. General purpose type cements usually have addition levels of 40-55% to ensure the setting time is within reasonable limits to allow finishing to be completed before the end of the day, or formwork to be stripped relatively quickly. Higher levels of slag addition are adopted for large pours where heat is a critical design issue.

- Sulfate resistance of concrete increases with the level of slag addition. BS 8500-1 Table defines the requirements for concrete to meet a range of sulfate ground conditions. All classes, except the most onerous (DC-4m) can be met using a CEM III/A slag cement (36-65% addition level). DC-4m class requires CEM III/B (66-80%).

- Many precast operations prefer not to use slag due to the extended formwork removal time or if required for durability enhancements, will adopt the lowest level possible (e.g. 36% if CEM III/A is required)

- There are many other durability advantages (e.g. Delayed Ettringite Formation and chloride migration resistance) which can influence the slag addition level.

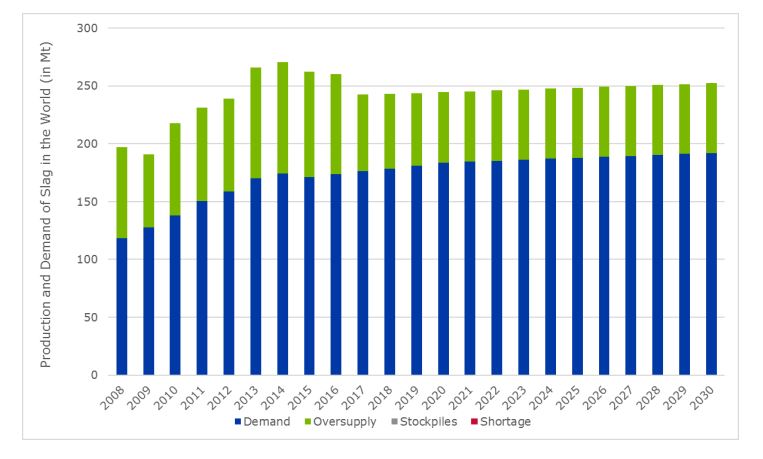

Unfortunately, there is a recognised shortage of supply of slag and the situation is deteriorating as the manufacturing of steel from iron ore is switching from blastfurnace to the less energy intensive electric arc furnaces. From a UK perspective there is very little fly ash available and slag is increasingly being imported from around the globe (e.g. from Spain and even Japan). Global cement production is around 4.1 billion tonnes per annum, which the Global Cement and Concrete Association estimate to equate 14 billion cubic metres of concrete. Annual slag production is 250mT of which around 170mT is ground into a cementitious material (the remainder is allowed to air-dry to form a lightweight aggregate). Increased grinding could see slag levels at around 200million tonnes/year. There is plenty of anecdotal evidence that slag shortages are impacting the market. In the past few weeks the author has spoken to or been informed that:

- A flooring contractor has been advised that slag will not be available in the summer by their concrete supplier.

- A bagged cementitious product supplier is reformulating their mixes to eliminate materials in short supply

- A ready mixed concrete supplier is only producing mixes with slag when required for technical reasons (e.g. sulfate ground conditions) .

The use of low carbon concrete is actually increasing global CO2 emissions.

The situation with fly ash is different in so much there is unused production. A report commissioned by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) identifies that there are larger volumes of fly ash available (circa 600mT with approximately 200mT used). However, most of this fly ash is in China, India and the US.

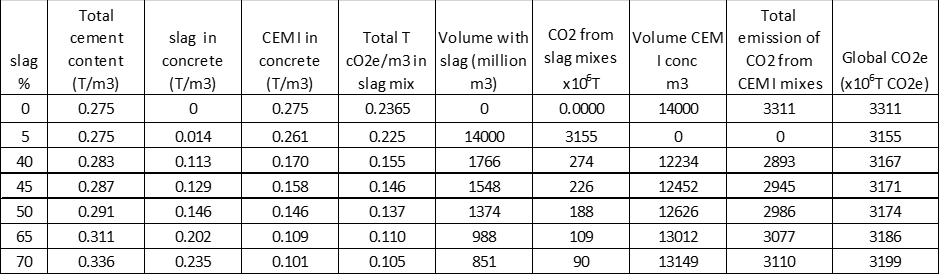

With 14 billion m3 of concrete produced annually and say 200mT of slag available we can theoretically add a meagre 14kg of slag to each cubic metre of concrete. At such a low addition rate, none of the performance advantages of slag would be realised. If we assume the average cement content for CEM I is 275kg/m3 then 14kg is only 5%, which is so ow that the material would still class as CEM I according to EN 196. If 40% slag was used, there would be a small increase in total cement content to maintain the characteristic strength at 28 days compared to a concrete made with 100% CEM I and there would be sufficient slag to produce 1766 million m3 while the remaining 12234 million m3 (see Table 2) would need to be produced with CEM I (as all the slag has been used). Using these volumes to calculate CO2e and just considering cement for simplicity, gives some interesting results.

As illustrated in Table 2, the maximum CO2e emissions occur when 100% CEM I is used. However, as the percentage of slag content is increased (i.e. lower levels of carbon in the concrete), the level of global CO2 emissions increases (Figure 3). The use of low carbon concrete is actually increasing global CO2 emissions.

The industry’s current addiction to high levels of slag is causing all sorts of problems:

- It is causing supply chain issues

- Costs are increasing

- Extended setting times are causing problems for contractors on site

- Is undermining the precast industry

- Construction programmes are being extended

- Innovation in alternative SCMs is being stifled

It could be argued, that these problems are acceptable if it means we are helping tackle the climate crisis but to impose them to effectively increase global CO2 emissions is frankly perverse. The situation is made worse when alkali-activated cementitious materials (AACM) with even higher levels of slag are used. The LCCG Benchmarking system (figure 1) will exacerbate these problems because the only real way to move towards A++ is to use high levels of slag. The Routemap does caution about the global emission problem but still sees using high levels of slag as the short term solution.

A completely different picture of the carbon situation emerges if the impact of this shortage of slag is taken into account in carbon calculations. If concrete mixes are produced with additional slag content over and above that necessary for efficient design, then somewhere in the world, concrete will by necessity need to be used without slag. Economists are well versed in accounting for resource scarcity through the use of opportunity costs, which can be defined as the potential benefit given up by choosing one option over another. The same principal applies to slag in concrete. There is a shortage of these materials so if used in one concrete it is unavailable for another. This would be a neutral effect, if slag was simply preferentially used on one site instead of another except the trend is to use slag in larger and larger quantities to produce “ultra low carbon concrete” leading to significant opportunity carbon costs.

The analysis in Table 2 shows that the optimum level of slag addition for purely sustainability reasons is very low, providing this low amount is used in all concrete. In practice this is never going to occur and it would waste the undoubted performance benefits of slag in concrete but the general principle that lower slag contents will reduce global CO2e should be observed.

A benchmark level for the addition of slag needs to be defined. I have selected 40%because this will produce a good general purpose cement, able to provide an effective alternative to CEM I. This level should be sufficient for much of the performance benefit from using slag to be realised but should be low enough to ensure that the limited valuable resource is not over used in a false pursuit of low carbon concrete.

The difference between the slag content used and the slag content at the benchmark is the basis for determining the opportunity carbon cost. As an example, C40/50 concrete could be produced with a blend of 40:60 slag:CEM I or 70:30. As illustrated in Table 1, the total amount of slag used in the two mixes could be 290kg (at 70% slag) instead of 140kg (at 40% slag). There is clearly a lost opportunity for the 150kg difference which is now not available for use in other concrete. This other concrete will still be produced, the difference will be that it will use CEM I in lieu of 40% slag (the aggregates, the 60% of the total cement content which is CEM I, mixing, haulage etc will be required whether slag or CEM I is used). Since concrete with slag requires a higher cement content to achieve the same characteristic strength, then the 151kg should be factored to acknowledge the CEM I mix will have a lower total cement content. Assume a typical difference of 3-5%, a factor of 0.95 has been applied to give a value of 143kg for the additional CEM I required producing an opportunity carbon cost (oppCO2e) of 123kg CO2e. Adding the oppCO2e to the calculated CO2e of the mix of 139kg gives a total CO2e (totCO2e) of 262kg in the higher slag content mix (see Table 3).

Accounting for opportunity carbon has made the 40% option the most sustainable. This may not always be the case, as illustrated in Table 4, when a lower strength concrete and a DC-3 classification for sulfate resistance (see BS 8500) which brings in requirements for minimum cement contents and maximum water cement ratios.

From these examples it can be seen that the use of opportunity carbon can reorientate the calculation of embodied carbon, such that using high levels is not the sustainable solution. However, a careful balance needs to be struck as the desired outcome of the inclusion of oppCO2e is to use ggbs effectively, not switch all production to CEM I.

Fly ash does not have the same problem as slag because as stated previously there are excess quantities of the material available, and its wider use should be encouraged. Furthermore, it tends to be used in a small addition range, typically 25-35% and is not used in large quantities just for low carbon objectives. and therefore no opportunity carbon cost should be levied on fly ash. Likewise at this stage the same is true for other potential SCM like limestone fines, calcined clay, EMC, conditioned fly ash etc.

The LCCG Routemap contains the chart reproduced in Figure 3, which shows the critical period for addressing climate change is in the next 15 years. Sadly, because high slag concretes are perceived as providing low carbon concrete and they can be acquired if the purchaser is willing to pay enough, these products are being wasted in a misguided attempt to address climate change. Instead of trying to find ways of adding increasing quantities of slag to concrete , the industry should be looking to accelerate SCMs like calcined clay and EMF to market By using these materials, real CO2 reduction is possible, but the wasteful use of slag to produce “low carbon concrete” that isn’t, is effectively kicking into the long-grass investment in these alternative SCM that could make a real difference. If we wait for the time slag becomes unaffordable or unavailable to tackle our addiction it will be too late.