I’ve been thinking about sustainability and specifying concrete a lot recently (yes I know I need to get out more!), particularly low carbon concrete and my increasingly strengthening opinion is that we’ve got it badly wrong. I’ve been reviewing the draft Low Carbon Concrete Routemap, prepared by Green Construction Board’s Low Carbon Concrete Group (LCCG) and while it contains many good points and highlights my major concern, which I will come to shortly, it’s proposed solution will make matters worse (in my humble opinion) by increasing global CO2 emissions.

I fear that many low carbon concretes, geopolymers and alkali-activated cementitious materials are modern day snake oil, marketed to be the ultimate in environmentally friendly products but in fact are an expensive way to make matters worse.

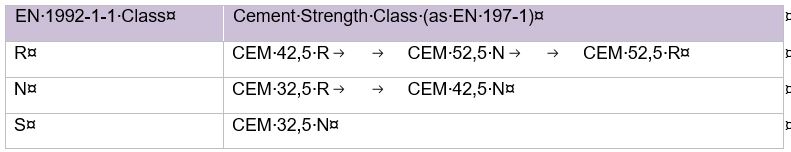

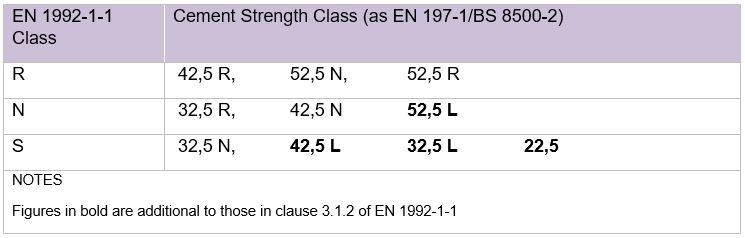

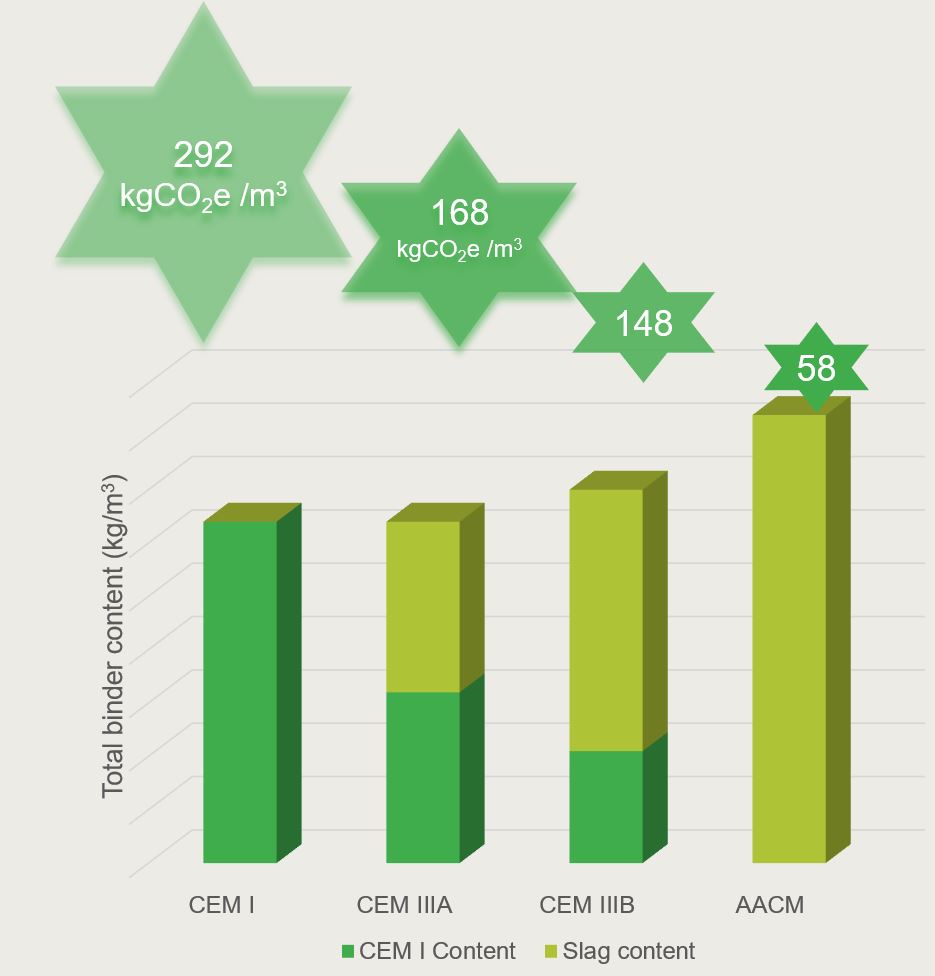

We are used to specifying concrete with supplementary cementitious materials (SCM) like ground granulated blastfurnace slag (a by-product from steel production) or fly ash (from burning coal to generate electricity). As these materials are effectively waste products generated from other processes, they have very low embedded carbon contents and therefore when blended with CEM I, to produce CEM III/A (typically 40-50% slag), CEM III/B (typically 70% slag), CEM II/B-V (typically 30% fly ash) or an alkali-activated cementitious material (up to 100% slag), they significantly reduce the carbon content of concrete as illustrated below for a C32/40.

When concrete is made using slag in a CEM III/A cement, it is generally produced with the same cement content as a concrete using only CEM I. If the slag content is increased to 70%, then to achieve the same 28 day strength the concrete needs a slightly higher total cement content (approximately a 10-15%) to compensate for the slower strength gain from slag cements (unless it is possible to specify a 56 or 90 day compliance age). Alkali activated cementitious materials using over 90% slag often need a significant increase in binder content to maintain an equivalent strength (25-35%). However, due to the low embodied carbon attributed to the slag compared to CEM I, then significant reductions in carbon are achieved despite the increase in binder contents.

So all is well and good. We could save 110 kgCO2e/m3 by switching from CEM III/A to AACM and we will be taking our DJs and posh frocks to the dry cleaners in preparation for the sustainability awards we’re bound to win. But wait, is that a butterfly I hear flapping its wings in the Amazon, is there about to be a tornado in Texas? Chaos theory tells us everything is linked and a small change in one part of the system can lead to significant changes elsewhere. Similarly, climate change is not a UK issue, it’s a global issue and we must think globally.

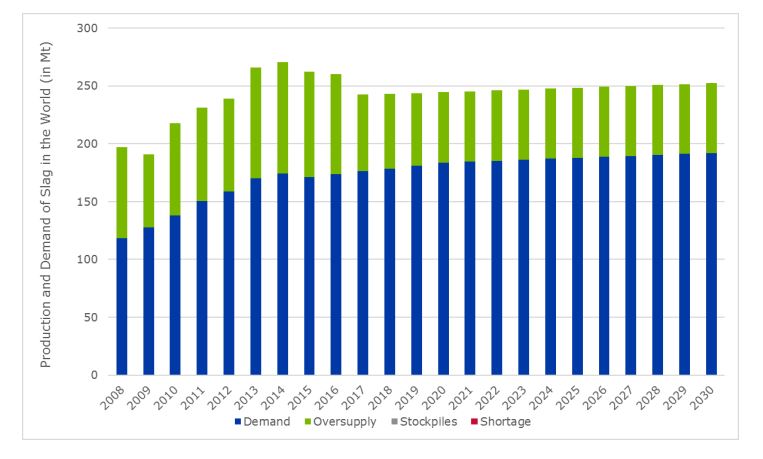

Annual global cement production is around 4.1 billion tonnes, which according to Global Cement will make approximately 10.1 billion m3 of concrete. To switch all CEM I to the environmentally friendly CEM III/A, we would need around 2.0 billion tonnes of slag. To convert all to AACM would require 5.4 billion tonnes of slag. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) commissioned a report to look into the availability of fly ash and slag for cement manufacturing. The BEIS Technical Report 19 concludes that there is a global surplus of slag (see figure below). However, there are a number of assumptions in this data, the most significant being a factor of 4 is applied to account for the fact slag application is relatively high in the UK compared to the rest of the world. There also does not appear to be a separation of slag used for cementitious purposes and slag used as aggregate.

The BEIS report identifies that there are larger volumes of fly ash available (circa 600mT with approximately 200mT used). However, most of this fly ash is in China, India and the USA, away from the coast and consequently not readily available for shipping. Even if all the fly ash and slag in the world was available for use in concrete (which it clearly is not) it’s less than 20% of the cement production and in reality far lower than that.

Both materials are facing a long-term decline in production. While COP26 had a last minute softening on the aspiration to phase-out coal-powered electricity generation and weakened it to phase-down, the trajectory is clear and in most major construction markets the local availability of fly ash will decline. The switching of iron manufacturing from blast furnaces to lower carbon, slag-free electric-arc furnaces will see a decline in slag production.

The actual availability of slag and fly ash is probably around 5-10% of cement production. The limitation in slag and fly ash supplies means that if slag or fly ash is used on one site, then somewhere else concrete will need to be produced without any slag (i.e. just CEM I). Let’s look again at our saving from using AACM. Let’s assume a total slag content in the AACM of 420kg/m3 and 160 kg/m3 in the CEM III/A. With 420 kg of slag we can make 1m3 of concrete with AACM or 2.6m3 of concrete with CEM III/A. To bring the AACM production up to the same level as CEM III/A we will have to produce 1.6 m3 of concrete with CEM I.

Do the math as our American colleagues would say and we have:

For CEM III/A

2.6 x 168= 436.8 kgCO2e/m3

For AACM and CEM I

1 x 58 +1.6×292 =525.2 kgCO2e/m3

An increase in global CO2 of 88kg/m3 or 20%. I’m sure we could debate all the figures I’ve used here but I’m convinced no matter how you tweak them, the use of low AACM that rely on high levels of addition of slag will produce a global increase in CO2 levels. I accept my argument relies on slag and fly ash being fully utilised but even if there is some under utilisation then surely it is far more sustainable for that slag or fly ash to be used in or close to its country of origin rather than being hauled from deepest China to the UK and we certainly should not be increasing binder contents in the name of sustainability. Our goal should be to reduce binder contents by reviewing our designs, specifications, standards, structural designs and any other means possible.

Back to the LCCG routemap. There is recognition in the document for the situation I describe. Section 5.2 is headed “Use supplementary cementitious materials other than GGBS and fly ash where possible” and goes on to say

“The use of GGBS or FA to replace some of the Portland cement in a concrete will reduce the carbon footprint of an individual mix. However, since the national supply of GGBS and FA is fully utilised, use of GGBS or FA in any one mix may not reduce overall global greenhouse gas emissions”

Routemap to Low Carbon Concrete

What they have veered away from saying is that it may make matters worse.

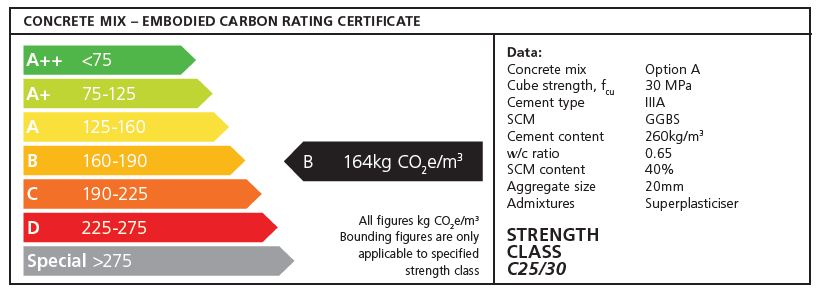

In the current version, the Infographic at the start of the document which illustrates the routemap, states that the use of fly ash and slag should be increased. I think a blanket statement along these lines is a mistake. The LCCG are also proposing benchmarking concrete with a scale similar to that we are used to seeing on white goods. Another mistake in my opinion. These two headline statements will encourage a race to low ratings and whatever it says in a paragraph on page 44 of the document, that will be driven in the only way currently practically possible, i.e. by increasing fly ash and slag contents. Yet in the LCCG’s own words, it may not reduce overall global greenhouse emissions.

Slag and fly ash are vital ingredients for producing durable concrete yet it is a resource that will only diminish. These supplementary cementitious materials:

- Improve the chloride resistance of concrete

- Improve the sulfate resistance of concrete

- Help resist delayed ettringite formation and alkali-silica reaction

- Reduce temperatures in large pours helping to reduce the risk of thermal cracking

- ….and much more.

However, there are also negative aspects. Ask any contactor what they think about high levels of slag in their concrete and you may get a very flowery response littered with some ancient Anglo-Saxon terms, particularly at this time of year as the temperatures drop. The slow setting of the material is accentuated and construction programmes are delayed as formwork striking times are extended and concrete gangs work late into the night waiting for concrete to set so they can apply a finish. Measures to counter the cold weather are then taken. Space heaters may be introduced on site or concrete grades are increased to put more cement in the mix to speed-up strength gains. All measures which increase the carbon footprint of the project.

All these measures and problems would be worth it if the use of SCMs were making a difference in the fight on climate change, but as I keep saying, they’re not. At best they are making no difference to global CO2 emissions and at worse, will increase them.

We should not be throwing slag and fly ash into concrete to chase an arbitrary meaningless rating, instead we should be treating them as valuable resources and use them in situations where their thermal and durability properties are most needed.

I’m not advocating doing nothing, although that would be better than using high levels of slag or fly ash. There are materials in plentiful supply that could be used. There are lagoons full of conditioned fly ash which could be utilised, limestone fines are widely available and calcined clays could be. All have drawbacks and problems that will need investment and effort to overcome so we should be looking to ways to incentivise this approach. These materials are all discussed in the LCCG Routemap, but because slag and fly ash remain the easy option in the document, there will not be any focus on the more difficult and sustainable alternatives.

I’m going to make a radical suggestion, that will probably go down like the proverbial bucket of cold vomit. The idea needs more thought and work, but I think it could form the basis of the way forward.

- Fly ash and slag have a lower carbon content than CEM I and their use should be maximised but preferably near their country of origin and in applications where their durability properties are required.

- Let’s accept that the arbitrarily shipping fly ash and slag around the globe doesn’t reduce the global CO2e figure for concrete

- Calculate the CO2e of concrete on a global basis (see equation below)

- Use this figure for any type of cement that incorporates normally sourced fly ash or slag and for CEM I. This means there will be no sustainability advantage for using slag or fly ash.

- When conditioned fly ash, limestone fines, calcined clay or other plentiful supply or under utilised material is used in cement production, use the product specific value, which will lower global CO2 contents and can therefore be positively recognised in the LCCG’s benchmarking system.

where

XXX eCO2 is the embodied carbon per tonne of the material based on a global assessment

XXX gb.usage is an estimate of the global usage of the material

I don’t want to get bogged down in to a discussion on how to derive these figures, it’s the general principal I’m trying to establish but I imagine it would give a figure somewhere in the low 800s kgCO2e/T.

I see this as having the benefit of stopping the use of large percentages of slag and fly ash for sustainability rather than durability reasons and will encourage innovation in low carbon concrete that might make a real difference to global CO2 levels. The LCCG’s benchmarking proposals will also work better with this type of approach.

I also believe we over specify concrete for strength and in some cases durability and that we should be looking to use less cement as well as lower carbon cements and pursuing lean designs but that will be the subject of a future posting (this one is already long enough!).

There is much to do if we are serious about tackling concrete’s impact on climate change and ditching the snake oil is a good place to start.