We just love to classify things.

- Our social status (upper class, middle class , working class)

- Our cars (MPV, saloon, mini, hybrid, estate etc)

- Our bread (granary, wholemeal, sourdough etc)

I quite liked this classification of science.

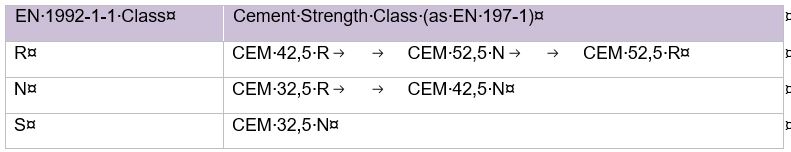

The classification of cement in various standards has caused some confusion amongst colleagues so I thought I’d share my conclusions with you. Eurocode 2 uses a simple classification system when calculating early age strengths, creep coefficients or drying shrinkage strain. Depending on the rate of strength gain, concrete is classified as either Class R, N or S.

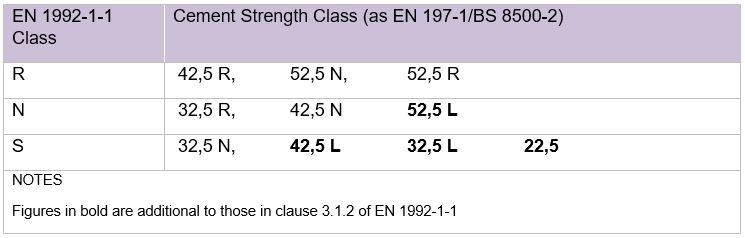

The European cement standard, EN 197-1 uses a similar classification system. Until the November 2011 amendment of EN197-1, the standard only had two classes of early strength for each standard strength class – cement with ordinary strength gain indicated by N and high early strength by R. The 2011 revision introduced a third category “L” (I suppose “S” would have been too obvious!).

The introduction of Class L at least brought EN 197-1 in line with the complementary British Standard to EN 206, BS 8500, which also uses the designations Class R, N and L.

I hope you’re following this as it’s about to get more confusing. The table below reproduces the cement classes given in clause 3.1.2(6) from EN 1992-1-1. The list of cements does not cover the full range of cements in EN197-1 or the range typically used in the UK. Furthermore, it is immediately clear from Table 1 that the classes used in EN 1992-1-1 do not correlate with the designations used in EN 197-1 (e.g. CEM 52,5N is class R while CEM 32,5R is class N).

I need to add another standard in here, BS EN 14216 which covers the specification and performance of very low heat cements. There is actually close correlation between the definitions of R, N and L in EN 197-1, EN 14216 and BS 8500 but irritatingly there are some differences as shown in the table below (figures in brackets show the discrepancies between the standards).

From the Table above, it can be seen that a 32,5R has the same minimum 2 day strength as a 42,5N which helps to understand the logic of the classes used in EN 1992-1-1.

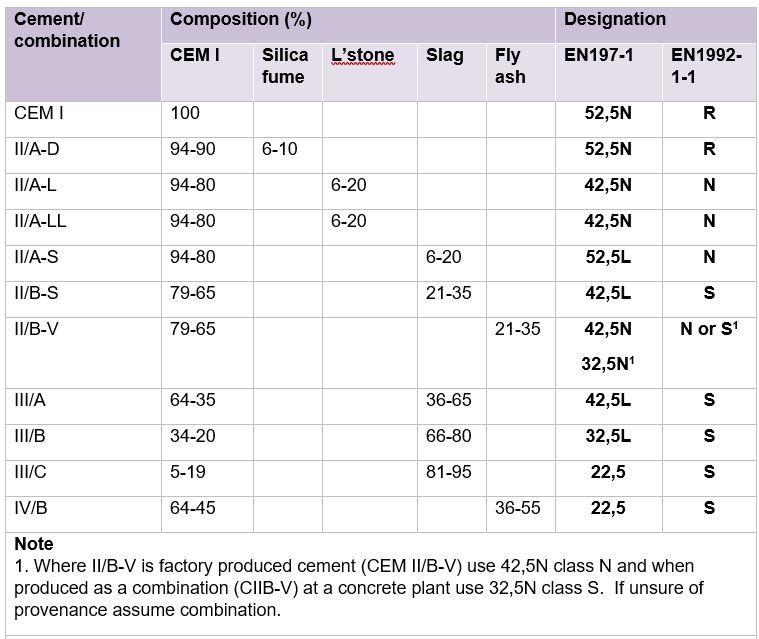

The question I often get asked is what class should be used for cements not covered in clause 3.1.2 of EN 1992-1-1. In the table below, I have extended the range of cements with my additions shown in bold.

Often full descriptions of the cement are not available and we may only know the generic type. I use the assumptions in the following table in those circumstances.

These are my own personal view and you are welcome to use them, but their use comes with no guarantees. Any comments?